For TIME MAGAZINE: Just a few weeks after Netflix surpassed 40 million customers, Blockbuster made public its plans to shutter their remaining 300 U.S. stores. The increased ubiquity of on-demand and downloadable movies played a large role in Blockbuster’s 2010 bankruptcy, and is largely credited with the swift decline of the video store industry for the majority of the past decade.

For TIME MAGAZINE: Just a few weeks after Netflix surpassed 40 million customers, Blockbuster made public its plans to shutter their remaining 300 U.S. stores. The increased ubiquity of on-demand and downloadable movies played a large role in Blockbuster’s 2010 bankruptcy, and is largely credited with the swift decline of the video store industry for the majority of the past decade.

Surprisingly, movie rentals are expected to rise, although customers are expected to use kiosks more and more to do so.

According to a June report by the market-research bible IBISWorld, there are approximately 10,000 independent stores in the U.S. that rent movies and video games — down from nearly 24,000 such operations in 2004. So what does this mean for the remaining independent video stores? Many of them consider financial subsistence a new reality of the business, and pin their hopes on an experience that can’t be matched by streaming services: a physical space for people talk and learn about movies, knowledgeable staffs, and vast catalogues of rare titles on VHS tapes and DVD.

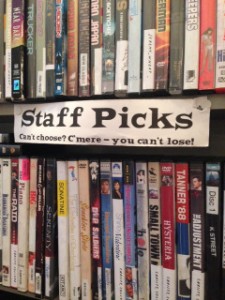

The key challenge is getting people in the door. Film screenings in the low-ceilinged basement of San Francisco’s Lost Weekend video store (pictured) draw meager crowds, so the owners offer their stage to stand-up comics several nights a week. As many as 35 fans turn up, pay a $5 or $10 cover, and buy some candy or a soda during the show. Profits are minimal, but over time, the shop has begun to see itself not just as a fledgling business but perhaps resembling what it used to be: a neighborhood social hub with cultural capital, according to store co-owner Christy Colcord.

“In the last five years, we have become more like a barbershop. People befuddled by all the change are coming in to talk,” said David Hawkins, another co-owner of Lost Weekend. “People are getting tired of sitting at home and having everything fed to them. This is a place to go and wander around. We’ve had people get married from meeting in here.”

Independent stores have been diversifying for years: Vidiots in Santa Monica runs a film studies center. Facets in Chicago runs its own film school, and a children’s film festival and film camp. Stores in Washington sell coffee and party supplies, while a Brooklyn store turned to selling gift boxes and passport photos.

When the Philadelphia-area video rental store he worked at for 13 years announced in the summer of 2011 that they were closing, Miguel Gomez borrowed enough capital to purchase the majority of their inventory and open his own store. Viva Video! has music events (Bollywood dance parties) and live film screenings in the alley outside the shop and in the store’s basement. He covers his expenses and is slowly chipping away at his loans.

“I have rare [Bernardo] Bertolucci VHS tapes I could sell for $300 on Amazon, but that doesn’t make any business sense,” Gomez says. “I feel a responsibility to aid the excitement of people to go see stuff.”

The independent video store conversation is global: shop owners in Australia argue that the depth of their movie collections and “curatorial expertise” keeps them alive. Since 2010, Vancouver’s video stores have experienced a small-scale revival. Decline in the U.K. mirrors the U.S.: roughly 760 independent video stores today, down from approximately 1,650 in 2004, according to IBISWorld data.

Bristol’s 20th Century Flicks has live music and hosts screenings of ‘80s Hong Kong horror-comedy movies in their tiny shop. They are stable but not profitable: they pull in roughly £200 (about $320) a day from rentals, a bit more on weekends. They’re considering streaming some of their more rare, obscure movies online as a way to expand their portfolio.

In a January op-ed titled “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Internet,” 20th Century Flicks co-owner David Taylor credited his store’s survival to a “small but loyal band” of clientele, and a dedicated staff that doesn’t earn much.

“The previous owner was going to chuck all these old movies away, so I started working for free just to save those films. I said to myself, I need these films,” Taylor says. “There’s about 3,000 of them, which is a unique selling point that might just give us a chance at something.”

Last month, Seattle’s Scarecrow Video — owned by a current Microsoft employee — had a big turnout for its celebration of the third International Independent Video Store Day, largely due to an announcement they made in advance that rentals had declined 40 percent over the past six years and that they may have to close. Scarecrow is considering a nonprofit business model, but the licensing and bandwidth required for online streaming is too cost prohibitive.

“There used to be these enormous conventions, where thousands of independent video store owners would show up and be wined and dined by distributors and labels, and Robert Altman or Bruce Campbell would do meet and greets,” said Kevin Shannon, Scarecrow’s general manager. “We used to count our revenue in dollars, now we count it in pennies. The customer has given up selection for convenience. My step-mom’s friends go to BitTorrent and get bootlegs, and I’m stunned. They’re 65 and that savvy?”

Photo by Gary Moskowitz