For the ECONOMIST: LAWS legalising same-sex marriage are (or soon will be) in effect in 17 states in America and in more than a dozen countries worldwide. These include Luxembourg, whose openly gay prime minister, Xavier Bettel, recently helped pass same-sex legislation that will go into effect early next year. Interpride, the umbrella organisation whose members organise gay-pride events around the world, reckons these occasions attract an estimated 20m participants and supporters.

For the ECONOMIST: LAWS legalising same-sex marriage are (or soon will be) in effect in 17 states in America and in more than a dozen countries worldwide. These include Luxembourg, whose openly gay prime minister, Xavier Bettel, recently helped pass same-sex legislation that will go into effect early next year. Interpride, the umbrella organisation whose members organise gay-pride events around the world, reckons these occasions attract an estimated 20m participants and supporters.

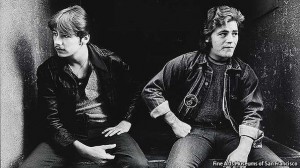

In 1969 when gay and lesbian communities were facing discrimination at work, violence and police brutality, all of this would have been incomprehensible. That was the year of the Stonewall riots, when gays responded to police harassment by rioting after a raid on the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in Greenwich Village. It was also the year a 19-year-old Los Angeles-based photographer named Anthony Friedkin began photographing gay communities in Los Angeles and San Francisco as part of a larger documentary project that became known as “The Gay Essay”, a series of photos spanning 1969 to 1973. He later went on to create photo essays on surfing, New York City brothels and California prisons.

To commemorate the 45th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, San Francisco’s de Young museum is exhibiting “Anthony Friedkin: The Gay Essay“, 75 vintage prints of Mr Friedkin’s portraits, taken in dancehalls, bars, streets, homes and hotels in California. The black-and-white images will be added to the museum’s permanent collection.

“I was very clear from the beginning that this was not meant to be objective photojournalism,” says Mr Friedkin. “This is a work of art. I wanted to validate their lives and experiences. And people allowed me to witness their very private, intimate moments. I tried to honour that.”

Using a Lycra camera (quiet, less obtrusive), Mr Friedkin photographed mixed-race couples, drag-queen balls in Long Beach, a lesbian couple in their Venice home, gay movie houses (sites of frequent late-night vice-squad raids), the cruising and hustling scene along Selma Avenue in Hollywood, dances at Troupers Hall in West Hollywood, the 1972 Gay Liberation Parade in Hollywood (and its religious protesters), an experimental theatre company in San Francisco, and much more.

European magazine editors typically embraced Mr Friedkin’s work, but he says it made some of his American editors nervous. “Editors thought it was cool, but were afraid advertisers would be upset about the more intimate photos.” He did not shy away from nudity: his portraits of a male hustler, which appear in the exhibition, are full-frontal.

In 1969 Mr Friedkin was finding his voice: his artistic parents, who gave him his first camera when he was eight, steered him away from being a “weekend artist” and encouraged him to take his art seriously. He had seen Robert Frank’s “The Americans”—diverse portraits of 1950s American life—and been moved by it. On hearing about the Stonewall riots, Mr Friedkin set out to create intimate, arms-length portraits using 35mm film. His goal was to make a collection of photos that showed people’s lives and experiences in a meaningful way. He ended up creating a record of a community finding its voice and taking a stand against sanctioned adversity.

“Teachers were fired for being gay, vice police would stalk bars, and women were arrested for ‘masquerading’ as men,” Mr Friedkin said. “They were being called sinners. I was angry about the pretentiousness of that.”

“Anthony Friedkin: The Gay Essay” is at the de Young Museum in San Francisco until January 11th 2015. The book will be published by Yale University Press in July.

Image courtesy of Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco