For the ECONOMIST: RECORD Store Day is a date for independent music shops in America and Britain to celebrate their existence and the music they sell. This year’s festival, which took place in April, has been hailed as a watershed moment in the renaissance of vinyl. Record companies marked the day by releasing nearly 500 new records in America and more than 600 in Britain. Some record-store owners reported opening their doors to hundreds of people who had been waiting in line from as early as 7am. And sales for the whole week were more than 50% higher than in the equivalent week last year.

For the ECONOMIST: RECORD Store Day is a date for independent music shops in America and Britain to celebrate their existence and the music they sell. This year’s festival, which took place in April, has been hailed as a watershed moment in the renaissance of vinyl. Record companies marked the day by releasing nearly 500 new records in America and more than 600 in Britain. Some record-store owners reported opening their doors to hundreds of people who had been waiting in line from as early as 7am. And sales for the whole week were more than 50% higher than in the equivalent week last year.

Vinyl sales so far in 2014 are the best they have been for ten years. The UK’s Official Charts Company predicts 900,000 vinyl albums will be sold this year in Britain, up from 790,000 last year. And in Nashville, United Record Pressing, a company that produces 30-40,000 pieces of vinyl each day, expects to double the volume it creates by bringing 16 new presses online by the end of the year.

Yet this momentum also brings problems. Smaller record shops don’t have the resources needed to handle the large number of records for a one-off day devoted to vinyl: they end up with “Record Store Day Graveyards” of albums they can’t sell. Pressing plants delay other orders (typically from smaller record labels) to handle the large quantity of records demanded for the annual event. And consumers can often be duped into thinking they are purchasing a rare, limited edition object, that simply isn’t.

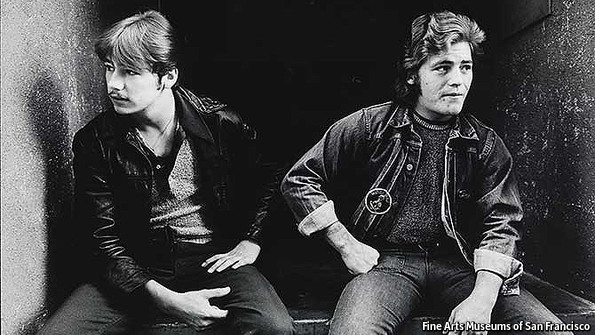

The rebirth of vinyl makes a timely backdrop for an interactive exhibit at the Oakland Museum of California called “Vinyl: the Sound and Culture of Records”, which aims to remind visitors that records, unlike mp3s, are tangible objects that can be collected, swapped, looked at and discussed in personal ways.

More listening lounge than exhibit, the show has rooms filled with crates of albums, turntables, pillows and personal stories—presented both in the written word and in audio—from record collectors and fans, primarily from the Bay Area. The collection of Michael Chabon, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author, titled “The Discography of a Nerd”, includes albums from Leonard Nimoy, the Alan Parsons Project, Rush and Parliament-Funkadelic. A crate filled by Dan the Automator, a hip-hop producer responsible for the debut album of the Gorillaz, includes albums from Eric B & Rakim and Dusty Springfield.

Visitors are invited to answer questions about albums, such as “What makes a good song?” (one response: “the people playing the music have to be trying hard”). One listening station plays a Beatles song in both digital format and vinyl, and asks visitors to see if they can tell the difference. During this correspondent’s recent visit, two guests flipped through crates of albums, and laughed about which ones were most important to them in their teenage years. Museum staff occasionally head to the turntables to put on records and dance. Songs from artists ranging from Steely Dan to Juan García Esquivel echoed through the room.

René de Guzman, the museum’s senior curator, said he set out to understand why the analogue technology of vinyl records was flourishing in the digital age, and why it now has a “hipster aura”. The exhibition does not explicitly answer those questions, but one-off events have created opportunities for personal testimonies and candid moments illustrating vinyl’s intangible value.

“There’s a social aspect of listening to records,” Mr de Guzman said. “You share musical interests and let others know the reasons why certain things are meaningful to you and others. Listening to records puts music into the foreground because its physical nature requires intention and attention.”

“Vinyl: the Sound and Culture of Records” is at the Oakland Museum of California until July 27th

Image courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California