For the ECONOMIST: JUSTIN KAUFLIN, a 24-year-old blind jazz pianist from Virginia, has had an enviable few years. He has won awards, reached the semi-finals of the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition, and toured with both Quincy Jones and the Jae Sinnett Trio.

For the ECONOMIST: JUSTIN KAUFLIN, a 24-year-old blind jazz pianist from Virginia, has had an enviable few years. He has won awards, reached the semi-finals of the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition, and toured with both Quincy Jones and the Jae Sinnett Trio.

In January he will release his debut album, “Dedication”. The 12 songs highlight Mr Kauflin’s nimble sound, but perhaps the most significant is “For Clark”. It’s a nod to the highly influential, Grammy-winning jazz trumpeter Clark Terry, who mentored and tutored Mr Kauflin for years, while Mr Terry himself battled with diabetes and lost his eyesight.

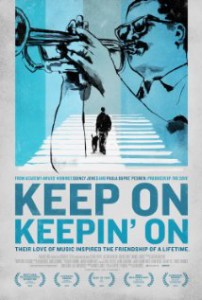

“Keep on Keepin’ On“, a new documentary directed by Alan Hicks, explores the relationship between Messrs Terry and Kauflin (pictured together above, Mr Terry on the right) over the course of five years. Both the director and Mr Kauflin were students of Mr Terry’s at William Paterson University in New Jersey and both played in the Clark Terry Ensemble.

“Keep on Keepin’ On” works its way steadily through the emotions: sadness as Mr Terry (now 93) and his wife struggle with his hospital visits and treatments; heartbreak when Mr Kauflin’s nerves get the better of him at the Thelonious Monk Competition; sincerity when Mr Terry speaks to Mr Kauflin about musicianship and adulthood; and joy as Mr Terry plays his music.

Mr Hicks demonstrates precisely how and why Mr Terry is a jazz giant: video footage shows his virtuosic capacity to play fast, upper-range hard-bop as well as airy, soulful, slow-tempo ballads. Photos and film clips show him performing with Count Basie and Duke Ellington, as well as the Tonight Show Band. In one brief clip, Miles Davis says, “Clark Terry was my first idol.”

The film also explains a key piece of Mr Terry’s background: the difficulty he had in finding mentors among the “unhelpful old-timers” he encountered as a young boy interested in the trumpet and in jazz music. As a result he vowed to be a teacher for younger musicians coming after him. The essence of his pedagogy, as portrayed in the film through interviews with him and some of his students, is simple but powerful: “Relax, reach way down deep in your soul” and “produce that which is in it.” Throughout the film Mr Kauflin struggles with this. “I have to figure out how to be me,” he says. It’s Mr Terry, curled up in hospital beds, who essentially gets him there.

One of the dominant themes of jazz today is its perceived stagnancy, conservatism and inability to draw in new listeners and musicians. Mr Hicks’s film veers away from these debates. It is not likely to increase jazz’s popularity. But the documentary—and Mr Terry himself—puts forward a compelling idea that is central to jazz no matter the era: sensitivity, humour, style and hard work still have the capacity to produce great music. Mr Terry’s efforts to convey this idea to Mr Kauflin are uninhibited and honest: “Straight ahead. Play your ass off.”

“Keep on Keepin’ On” is showing at cinemas across America until 2015