As the genre is declared Americans’ favourite, veteran musicians consider their legacy

As the genre is declared Americans’ favourite, veteran musicians consider their legacy

For the ECONOMIST: SOUTH BY SOUTHWEST (SXSW) may lure more than 250,000 people to Austin each year to learn about and experience technology, film and video gaming, but music has always been the festival’s raison d’être. Though indie rock has long prevailed, this year it was hip-hop that dominated both the conference rooms and the music venues. There was training and tutelage: young aspiring rappers participated in freestyle rap meet-ups and lined up to get career advice from celebrated managers. Newer artists looked at how the genre is evolving; experienced practitioners contemplated how far it had come.

This was partly prompted by the release of Nielsen’s year-end report on American listening habits in 2017. For the first time, hip-hop surpassed rock as the most popular variety, accounting for seven of the ten most-consumed albums. As listenership has grown—in large thanks to streaming services—so has the pool of talent. Hip-hop sub-genres have popped up on platforms like SoundCloud and YouTube, providing a huge volume of music.

But SXSW was also amplifying conversations about legacy that have been going on in the hip-hop community for some time. “All Eyez on Me”, a recent biopic of Tupac Shakur, was criticised for failing to capture the mythology of the man, and dismissed as “rarely more than a faithful adaptation of [his] Wikipedia entry”. Documentaries abound about his murder in 1996. When young rappers such as Lil Xan and Lil Yachty have criticised artists such as Shakur and Notorious B.I,G. as “boring” and “overrated”, the comments have been met with outrage. Long-time followers such as P. Frank Williams, an Emmy Award-winning producer and writer, stated that hip-hop cannot move forward without appreciating its past. Young rappers don’t always agree. In 2016, Lil Yachty asked: “If I’m doing this my way and making all this money, why should I do it how everybody says it’s supposed to be done?”

Skyy Hook, a radio presenter, was inspired by these public critiques to host a panel about Shakur’s legacy at SXSW. Rappers Money B, E.D.I. Mean and other panellists unanimously agreed that Shakur is one of the most talented rappers in the hip-hop canon, and that young performers need to appreciate the history of the music if they are to innovate.

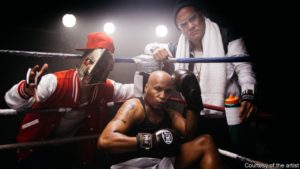

Other hip-hop creators told humorous and heartfelt stories about a life spent in pursuit of freedom, fame or wealth. Forbes interviewed U-God, a member of the Wu-Tang Clan, about the hip-hop collective’s rise to fame in the 1990s. Theodore Livingston—aka “Grand Wizzard Theodore”, a DJ—explained to the crowd that his mother is largely responsible for the invention of “scratching” and the needle drop, two techniques central to hip-hop music. Mr Livingston, 55, stated that his mother barged into his bedroom in 1975 to tell him to turn down his music, so he stopped the record from spinning on a turntable with his hand and moved it gently back and forth. (Some still find the story implausible.)

In tandem with this introspection, there is a growing sense that hip-hop is a subject worthy of serious study and reflection. Harvard University established the Hip-Hop Archive and Research Institute 16 years ago. In November, Stanford hosted a symposium dedicated to discussing the “liberatory possibilities” of hip-hop pedagogy in classrooms. Last month, the Oakland Museum of California opened “Respect: Hip Hop Style and Wisdom”, an exhibit that uses photography, video, art, music, dance and fashion to explore the genre’s cultural and social significance. The crowning jewel will be the Universal Hip-Hop Museum, scheduled to open its doors in 2022 in a 60,000 square-foot facility in the Bronx, where hip-hop originated. It will feature archives, exhibits, interactive displays, performances, film screenings and classes aimed at showing, explaining and discussing hip-hop culture.

The conversation, at SXSW and elsewhere, is about more than nostalgia. History has always been a huge component of hip-hop: “knowledge” is considered the fifth of five “pillars” of the culture (the others are graffiti, MCing, Bboying, and DJing). It has, from its inception, been a platform for black Americans and minority ethnic communities to give voice to their experiences of injustice. Shakur’s politicised, urgent lyrics often made reference to the Black Panthers, of which his parents were members, and the need to break free of oppressive governments and hypocritical notions of the American Dream.

As race relations have worsened in recent years, consumption of hip-hop has increased. “Alright”, Kendrick Lamar’s Grammy-nominated song, became a sort of de facto anthem for the Black Lives Matter movement, and Jay-Z’s Grammy-nominated album “4:44” explored racism and the black experience. Modern hip-hop musicians, whatever they think of their predecessors’ musical contributions, are similarly engaged in protest and speaking truth to power: the lyrics of early tracks still resonate. Regardless of how it innovates and changes, that will be hip-hop’s legacy.